Juris’s sympathy for the plight of the Viet Cong runs through “Red Flags,” but that, too, was evident from his earliest days in Viet Nam. He’d only been in country for a few weeks when he wrote this: “They were telling us how safe the replacement camp is the other morning when a mortar went off about 500 yards out. ‘As I was saying,’ the man continued, ‘the area is secure.’ Very funny. It really is safe though. 500 yards is about as close as those poor VC can get. They haven’t got the money to get closer. I guess that’s the advantage of being capitalists. I really feel sorry for these tenacious people. They’re holding off the whole big U.S. with not much more than pea shooters. And don’t let LBJ’s hearts and flowers speeches fool you, either. These GIs are trying their damnedest but at best they can make their own positions safe and maybe hold some of the country during the day. At night it all goes back to the Viet Cong while the Americans huddle together in their perimeters.

“You’ve got to respect these VC when you see how thick and ugly and barbed this thorny jungle is. It’s all the GIs can do to just cut the stuff down during the day. And the VC go right through it at night as if it weren’t there. How they do it no one knows, but it must be quite a grueling job to get through without cutting yourself to shreds. And every night they try — and get shot to hell as a flare goes off set off by a trip wire. The guards in the bunkers can’t even see them. They just spray everything and wait until morning to find out what or who they hit. And so it goes day in and day out – like some half-assed seesaw. If the sun just wouldn’t go down it would be okay. Too bad this isn’t the North Pole.

“And now to say my prayers and wish McNamara well. Heaven knows, he’ll need more than the old American dollar for this one. What a bill it is going to be.”

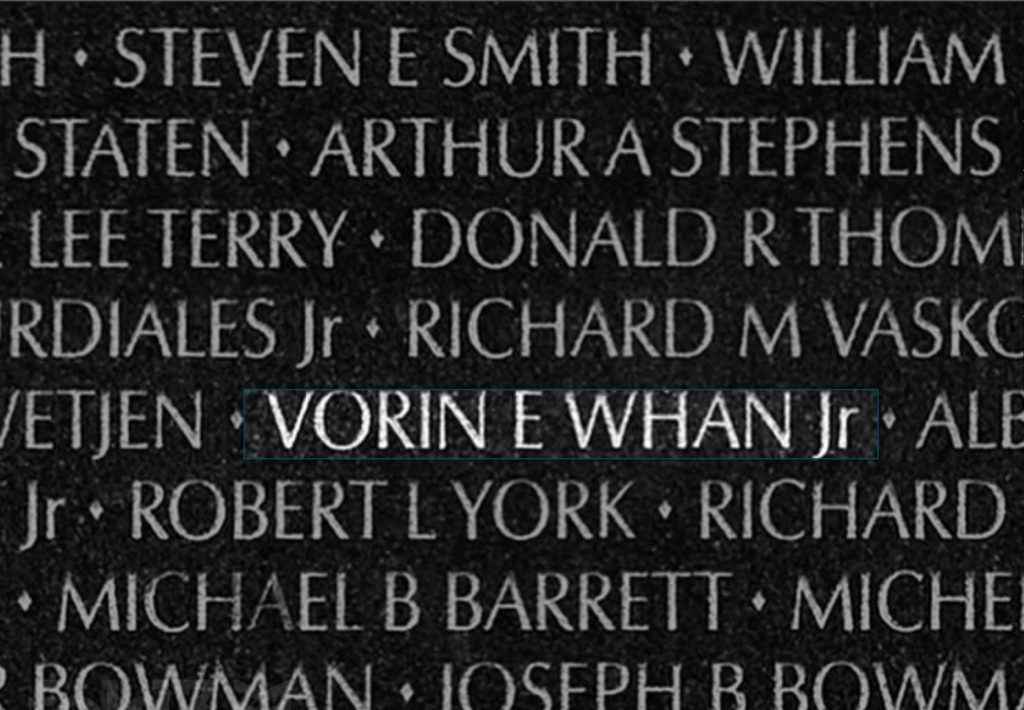

What a bill indeed. The American ‘solution’ to the problem of the jungle, Agent Orange, continues to take lives — both military and civilian — to this day. May, 2019, was the first Memorial Day we had to count Juris among the casualties of that war.