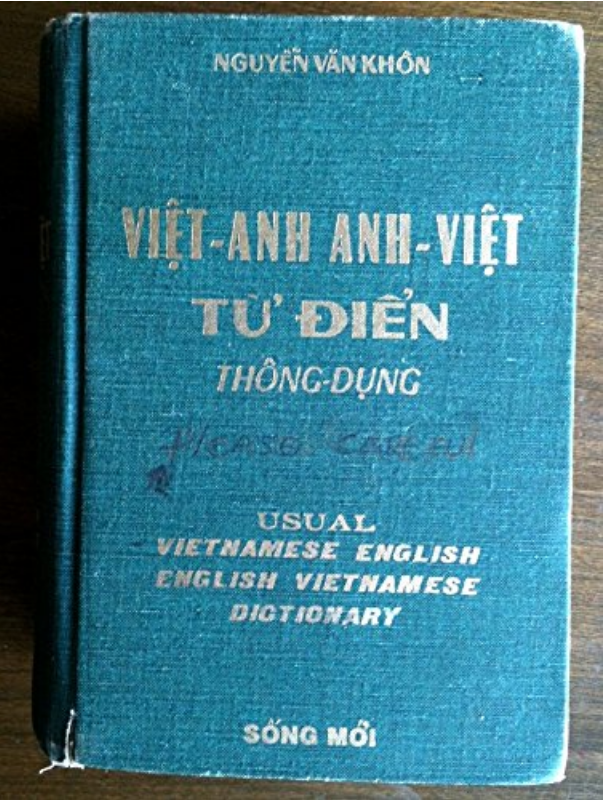

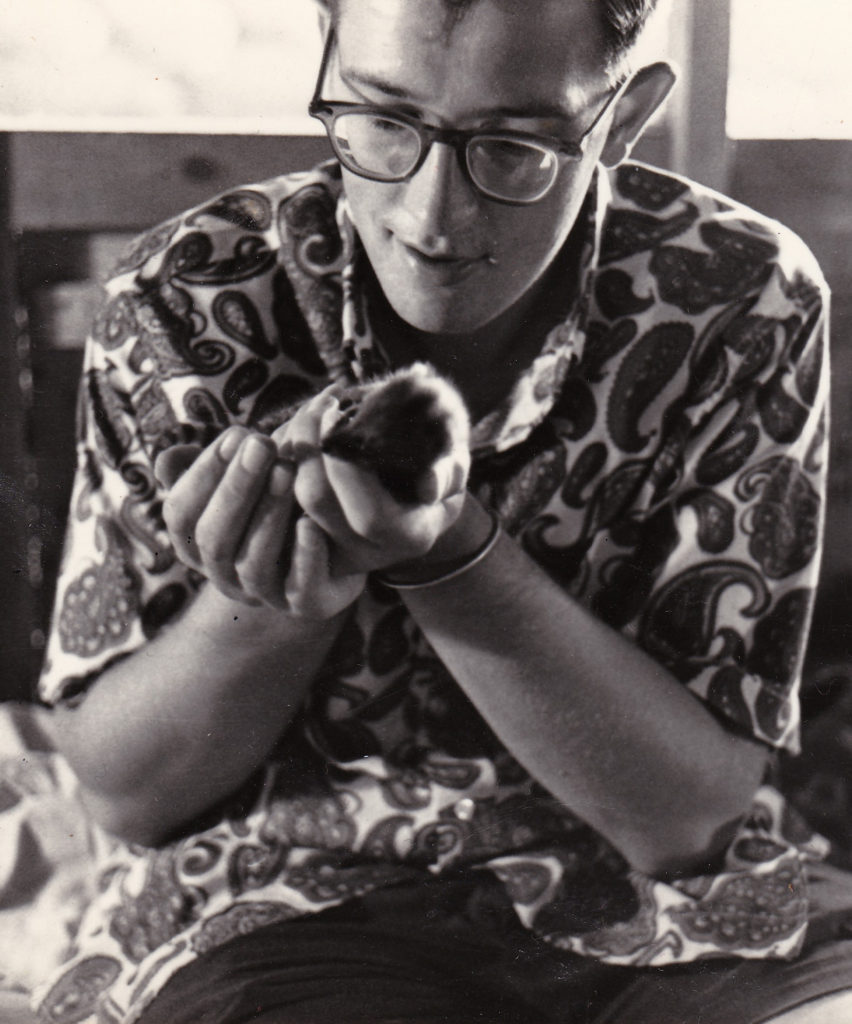

Not surprising to anyone who knew him, Juris became attached to children of all ages in Viet Nam. “Every other day I go down and tutor a Vietnamese kid in English. He’s a bright kid—seventeen—and unusually open for a Vietnamese, perhaps because he’s bounced around so much. Both his parents died some time ago so he has done quite a bit of that. Finally wound up here in Cheo Reo where his older brother (19) runs a small shop. I’ve gotten him some books (Viet to English) that they use in Saigon and a Viet-English dictionary. He’s an intelligent kid but his books and the stumbling efforts of his teachers are not too good so it’s awfully hard to tell how much he has learned. All I know is that he downright surprises me at times. I will soon have to leave him to his books and his own resources.”

A few lines from letters Juri received from his former student, who signed his letters “Your affectionate brother,” and “Your young brother” and “Your young brother Vietnamese”:

“My dear brother. You returned your country that is American one rich region. Do you have the please or the sorrow when you good-bye Phu Bon? I will be the sorrow, because the come day I do not see you, when I will go to New York? I don’t know.

“When you lived in Viet Nam what you saw the shadow of the war, you saw the wreckage because the bombs and the bullets.

“We are the people Vietnamese. We life on the small rigion of world. But we have the war, our house fall many persone die. Before day we have many rice, today we have few rice. That is a sorowfall shadow. It’s a war. The war is a hill. That day we will have the shadow of the war, the husband will to forget the wife, the baby will to die.

“VN’s war needing many soldiers. I may go to army in the vacance this year! My grand mother worry me too much.”

After Juri returned home, he tried to maintain contact, but after the fall of South Vietnam, he feared that any association with an American would put his student’s life in danger, and stopped.