The guys in the 101st Airborne liked their jokes dangerous.

The guys in the 101st Airborne liked their jokes dangerous.

In the spring of 1974 I was at the Gramercy Park Hotel attending my first sales conference as a senior editor with a major publisher. I had high hopes for a first novel I’d acquired and I was all kinds of revved. One of the nonfiction titles being presented at the conference — with the help of its handsome blond author — was the story of a former 101st paratrooper – enlisted — who went undercover after Vietnam, infiltrating the campus anti-war movement back home for the FBI. Bringing the author to the conference was unusual: a signal of a big investment and big expectations on the part of the publishing house.

The editor did his introduction and the well spoken author took over. Nothing he said sounded right to me. I tried not to listen, concentrating instead on my own upcoming presentations. I’d had the job less than a year; this was my moment to do it, put over a book I believed in. My jumping on this guy could look awful, hurt the firm’s bottom line, out me to the whole world as a Vietnam vet (risky in those days). Never mind humiliating and pissing off his editor – my brand-new boss. But my heart pounded with resentment. The guy’s pitch made me livid. The f-ing gall.

For six years I’d listened to Vietnam vets’ books being shot down as unsalable, the subject likened to cancer, and now this was going to be the book to break through? Blond white 101st paratrooper as heroic government snitch. What was wrong with this picture? The guy had no sashay, no swagger. Well scrubbed, wound tight. No peace sign on his helmet liner. Was I the only one not buying this story?

At the end, the author asked for questions. The staff was respectful and solicitous of the proper young veteran returned from the wars, only to risk himself again on the home front. Impulsively I raised my hand.

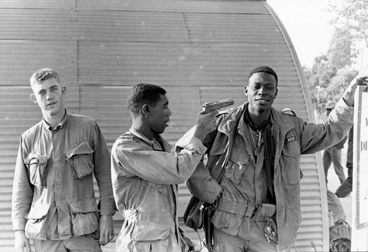

“The Airborne ranks were heavily black.”

“Yes,” he said, “somewhat.”

“What was the nickname of the 101st in Vietnam again?”

The memoirist looked uncomfortable. “The Screaming Eagles?” he said, the outfit’s well-known moniker inspired by the eagle’s head on the division’s emblem.

If I’d had any doubts, they were gone.

Sales reps a few seats away stared at my expression. “Isn’t that right,” one said quietly, “Screaming Eagles?”

I shook my head: “The 1st Afrika Corps.”

Afrika Corps — as in Rommel’s crack Aryan juggernaut of racially exclusive supermen in North Africa in WWII, outfighting and outwitting the allies for their racist Fatherland. GI humor, funny because it was dangerous: a slur and a backhanded salute all in one to the mostly black 101st.

Somebody got wise. The book slipped from the list a few days later, never to reappear.